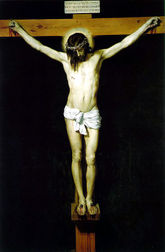

It is a mystical painting with sublime light falling on the body of Christ. Christ is painted in an almost upright position. He is presented as someone with a well formed, defined body. In this position and with this physique as someone who represents humanity in its fullness, it is as if the painting further reflects transcendence in portraying someone who ultimately is stronger than death, than the fate that seems to have overfallen him. There is no excruciating suffering here – tons of blood, tortured body, lashes, gashing wounds even though all the symbols associated with the story of the crucifiction are found in the painting – the crown of thorns, the wound in Christ’s side, the nails and the inscription. And, certainly, there is blood flowing from Christ’s wounds on the cross. Its serenity, its sublime character does not underplay the suffering and darkness of death. And yet, the focus is not on the suffering, but on Christ’s response to suffering. Looking at this picture, one does not feel sorry for Christ. He is not a victim of cruelty. Other, deeper and more emotions are evoked by what is being portrayed here.

It is a painting that, typically of its time, wanted to be precise and historically correct. Velazques carefully painted the cross so that it fitted the historical picture that scholars of his time reconstructed from the Gospels. The shadows that fall on the cross correspond to the time of the day that Christ was crucified. The wood of the cross is pine with its fine detail (the knots) and was at that time believed to have been the material used for the cross. With this precision the viewers are invited to stand before stark reality. This is what happens and what takes place when good and evil confront each other. You who view this work are involved in real life here.

Why am I so attracted to this painting? It represents a special perspective on the darkest night in the life of Christ. It captures a moment of complete stillness and loneliness, being the moment that he hung on the cross after the end of his life. He has reached the end of the journey. The road has ended. All creation has come to a standstill in this moment. It reveals the outcome of Christ’s life. It shows us what death does to him.

The body of Christ fills the canvass completely, but in such a manner that he at the same time also seems to be part of infinite space. Even though he is stetched out on the cross, the cross disappears completely behind his body. Only his hands and his feet are anchored to its beams. For the rest he seems to be standing before it in vast, open space (think Dali: where the cross hangs parallel with the heaven). The space behind him is completely empty – not a single object is depicted in it. The background is pitch black, bringing out in a dramatic manner the lightness that spills over the body of Christ. There are also no other characters in the painting (think: Rembrandt, the descent from the cross with the many disciples, so busy, so desperate, so grieving, removing the body of Christ). There are no thieves crucified with him, disciples or angels – often painted in those times on paintings of the crucifiction. All in all, Christ, this body, wrapped in gentle, enduring light and lightness, and not the cross, dominate.

The eye of the viewer falls, involuntarily, on the head of Christ as that which strikes us most about this body. The head of Christ is surrounded with soft, full light. The circle of light, the halo, above the head stresses the obscure face. It cathces the eye exactly because it is different to the light that covers the rest of his body. But there is an unusal facet to his head. It is slightly bent forward, hanging on his shoulder, almost as if in silent prayer. But it is his dishevelled hair that catches the eye of the viewer most. His hair hangs over and partially hides his face. One (barely) sees one eye and the nose of Christ – all other facial features are hidden in darkness. In this still moment, the moments of the death of Christ, his face is hidden – he is alone, on his own. A curtain is drawn, so to speak, before the unfathomable mystery that is being expressed here. He faces no one – does not look desperately and prayerfully up at the Father, nor searchingly at those around the cross, nor sorrowfully at the world. We cannot see death on his face. We see hiddenness, mystery, a drawn veil, the mysterium tremendum et fascinosum.

But in this solitude, in his complete loneliness in death, Christ is bathed in strong, beautiful, warm light. The moment of death is a moment of stillness, of unspeakable lightness. This man is dying a prayer, almost overstressed by his hands that are stretched out on this cross as if in a gesture of blessing the viewer. Peace be unto you. Let the mystery of light that surrounds me, even in death, fill and strenghten you.

Which leaves one with the question: early believers studied this painting in deep meditation. They saw a Christ, dying on the cross – a horrible death. But they also saw beauty, light. The darkness overwhelms – the body hangs serenely, bathed in luminous colours, in delicate light. Is the darkness the conquerer? Is the light the stronger one? It is a constant duel between darkness and beauty. Even as we expire, as our head sinks on our shoulder, as pain overwhelms us, we can be bearers of light.

That pain and that beauty are the constant reality of our lives, they are our companions as we continue the journey of our life.

Finally, the picture of Christ points to his uniqueness. He alone, only He can suffer with such serenity. Only he can be crowned with a halo, can reveal his divinity on a cross. His beauty in death, is an indication of a true, strong rejection of and protest against violence, against inhumanity that characterize those who life outside God. It is the perfect combination: this man of light, this strongly painted body, who also has blood oozing from the wounds. This man who died, whose head rests softly on his shoulder, this man is truly different. You see the hair of a man, dishevelled, unruly almost, the result of his via dolorosa. But it is also the mystic face of the divine person who enters light after this way of sorrow. Hidden from the sight of humanity, kept in the dark, is the immense power of the one who walks a different path than the road of violence. There is more light, there is true power in powerlessness, in saying no to hardness, to hatred, to the tough, clenched fist – in blessing the world prayerfully as it shakes its fist at him. He invites you to love his way, to love his peace, to follow him, to cry out against darkness and evil. His quiet serenity is a call to a deep, lasting emotional bond that brings the true light in darkness. It fills your inner being, floods it with feelings of adoration and beckons you to walk the same way. And, as you walk in the darkness, the light of this figure and the love that he emits, makes you strong in your weakness. The meek shall conquer the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.