Sport speel ‘n buitengewone groot rol in ‘n samelewing. Dit gee mense plesier. Dit bind gemeenskappe saam. Dit hou mense gesond. Dit is pragtig om te sien hoe behendig mense kan wees en met watter vaardighede hulle uitblink.

Sport is ‘n uitsonderlike gawe aan mense. Wie religieus daaroor wil nadink, sou selfs wou sê dat sport wys met watter uitsonderlike talente God mense kan seën en watter belangrike redes presterende atlete het om hul Skepper te loof vir gawes wat hulle ontvang het.

Sport het 'n lewensbelangrike rol te speel. Dit is vir vele die pad na geluk. Dit bring bevrediging om lekker moeg na ‘n tydjie op die veld, die fiets, die baan of die gimnasium rustig te kan ontspan en weer met al die bedrywighede van die lewe aan te gaan.

Daar is iets betowerends aan die manier waarop ‘n mens deur sport jou volledig aan die lewe kan oorgee.

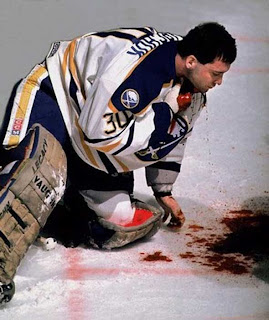

Sport, besef ek vanoggend toe ek die onderstaande berig in die New York Times lees, het sy vele skadukante. Een daarvan is wanneer sport vir mense bloot net ‘n middel is na iets anders, soos rykdom en roem. Om bo-uit te kom, is geen prys hoog genoeg nie. Dink maar hoe mense hul liggame dryf en watter houe hulle verduur. En hou maar in gedagte die vele jongmense wat met stimuleermiddels soos kreatien hul liggaam wil bou ongeag die mediese risiko’s daaraan verbonde. En dink net hoeveel sportlui uitgelewer is aan adminstrateurs en afrigters wat hul talente gebruik vir ander doelwitte as net die blote geluk en vervulling van die sportlui.

Dit alles hang nou saam met ‘n bepaalde dimensie van sport: Sport wakker naamlik stryd aan. Dit gaan om te bewys dat jy beter is as jou opponent. Jy verslaan mense teen wie jy meeding.

Daarmee is niks verkeerd nie. Goeie kompetisie bring die beste in mense voort.

Dit word verkeerd wanneer die stryd destruktief is. Daarom was daar in die groot sportlui van alle tye altyd ‘n ere-kode. Hoe jy ook al oor jou teenstander seëvier, moet dit altyd met erkentliheid gebeur omdat jy sonder jou teenstander nie die genot van sport sou kon ervaar nie. En, des te meer omdat jou wen van vandag jou verloor van môre kan voorafgaan. Hoogmoed kom tot ‘n val, sou byvoorbeeld gedurig in die agterkop van ‘n sportmens moet wees. Of, die held van vandag is die toeskouer van môre – daarom moet ‘n mens ook gedurig daaraan dink watter reputasie laat jy agter. En so sou ‘n mens vele ander gedagtes hieroor kon aanroer.

Sport begin in vele opsigte soos die besigheidswêreld sy integriteit kwytraak. Sportsmansgees is ‘n rare verskynsel. ‘n Mens hoor nie soveel dat ‘n mens sport speel om dit te geniet en om gesond te bly nie. Daar is samespanning om wedstryde te verloor. Daar is korrupsie in die finansiële administrasies van sportverenigings. Daar is onreg in die kies van spelers. Om nie te vergeet van die verskriklike tonele wat hulle by skole-sport afspeel wanneer ouers langs die veld en kinders op die veld hul menslikheid verloor.

Een van die opvallende dinge is die manier waarop mense gedryf word om op ‘n onverstandige manier hulself te benadeel. Hier is ‘n berig wat vertel hoedat spelers liggaamlik aan uiters onverstandige pratktyke blootgestel word. Die berig het my herinner aan ‘n onlangse televisie-program oor die gebruik van kreatien deur sportlui.

Die sake is ‘n tydige waarskuwing vir bietjie nadenke oor die veiligheid van spelers. En sommer ook oor die spiritualiteit van sport. Want in sport gaan dit steeds weer om ‘n saak waardeur mense tot gesonder, volwasser lewens getransformeer word. Waar dit nie gebeur nie, verloor sport sy wonderlike opbouende karakter.

Thirty-six years ago, Clark Booth, a young Boston journalist, went to Miami to cover Super Bowl X. Though primarily a television newsman, Booth was on assignment for The Real Paper, an alternative weekly long since closed, for which he often wrote. His plan was to interview the players about the potential consequences of the injuries they suffered playing football.

Today, on the eve of Super Bowl XLVI, everyone knows about those consequences. Thanks, in large part, to the groundbreaking work of Alan Schwarz of The Times, the National Football League has gone from minimizing the lasting damage that repeated concussions can cause to instituting rules about how soon a player can come back after suffering a head injury. Former players have filed class-action lawsuits against the league, claiming they suffer permanent brain damage as a result of concussions sustained while playing football. Stories recounting the lifelong toll of football injuries are common.

But no one had ever written an article like that before Clark Booth went to Miami. I remember being thunderstruck reading it. D.D. Lewis of the Dallas Cowboys talked about having nightmares and his fear of breaking his neck. Lee Roy Jordan, a veteran Cowboys linebacker, was asked by Booth why he kept playing with a sciatic nerve condition.

“By the time I’m 55, I feel they’ll have learned enough to medically treat me,” he said. “If they can’t, I can accept that.”

Booth asked sportswriters and ex-players about the worst injury they had ever seen. The stories he heard were almost too gruesome to read. He wrote about Alex Webster, a former great for the New York Giants who had “developed a radical mastoid problem from repeated thumps to the head.” Eventually, Webster required surgery that “involved cutting off his ears and then sewing them back on.” He then developed middle ear problems.

“Why maim yourself?” said Irv Cross, the former player-turned-sportscaster. “I don’t know. You just do it.” Jean Fugett, a tight end for the Cowboys who made $21,000 that year, said, “Injuries are just like death to a lot of players ... death of a career ... death of all that a lot of them want in life. So you say, ‘I’m not gonna worry about dying. I’m gonna go ahead and live!’ ”

I never forgot that article. And a few weeks ago, I tracked down Booth, who is 73 and living in Florida. He dug up a copy of the article, entitled “Death and Football,” and sent it to me. It was every bit as powerful as I had remembered.

“It was different then,” Booth recalled, talking about how he got the story. “You had a lot more contact with the players than reporters do now. You could catch them in the bar, or the hotel lobby, or talk to them after practice.” When he asked players about injuries, he said, there would usually be a long silence, and then they would start talking about their most hidden fears and their deepest denial. Other players, overhearing the interview, would chime in with their own stories.

“I felt like I had opened a door that nobody had tapped before,” Booth said. “I was amazed at what they were telling me.” Other reporters who overheard Booth’s interviews were also amazed. But Booth never had to worry about being scooped. Sportswriters back then just didn’t write about subjects like whether concussions led to dementia. “They were fascinated,” said Booth, “but they had no use for the material.”

After talking to Booth, I tracked down one other person from Super Bowl X: Jean Fugett, now a lawyer in Baltimore. “Would I play football again if I could do it all over again? Probably,” he said. “But I cried when my youngest son took a football scholarship.”

Today, says Fugett, he can’t sleep more than three hours a stretch without feeling pain somewhere in his body. He has no idea, he told me, how many concussions he sustained; back then, “you didn’t take yourself out of the game unless you stuffed two ammonia tablets up your nose and your head didn’t jerk back. That’s when you knew you were really concussed.” And he views himself as one of the lucky ones. Most of the former players he knows live with far more pain than he does.

Thanks to rule changes aimed at lessening the chances of career-ending injuries, football is a tad less dangerous than it once was. But it is still a game whose appeal lies in its violent nature. You cannot play football at the professional level without having it affect — and quite possibly shorten — the rest of your life.

“I don’t think anyone should play tackle football before high school,” Fugett told me before getting off the phone. “Kids’ bodies are not ready.”

“Flag football,” he said, “is a wonderful game.”

Kyk ook die foto’s en veral die kommentaar by: http://thewondrous.com/18-horrible-sports-injuries-ever/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.